R&D

How much does it hurt-measuring pain in clinical trials

Most clinical trials for pain still use a zero-to-ten scale as a primary endpoint. William Newton talks to experts on the hunt for improvements or alternatives.

Pain is a complex and personal experience. Yet, for the better part of the past century, clinical trials for pain have relied on a simple primary endpoint: “On a scale of one to ten, how badly does it hurt?”

Clinical trials for pain using this 1-to-10 scale can have volatile results that are difficult to reproduce in larger studies. Pain can also manifest in many different forms—from acute knee pain to chronic back pain—making it ill-suited as a one-size-fits-all endpoint.

“We're trying to compress a multi-dimensional experience into a single straight line bounded on two sides,” says pain trial researcher Dr Nathaniel Katz, associate professor of anaesthesia at Tufts University. “It's a very artificial exercise.”

Some researchers are developing new pain outcomes tailored to specific conditions, including a soon-to-be-published Journal of Pain article with FDA collaboration. Others are working to improve the existing 1-to-10 outcome through patient training modules or improved monitoring strategies. For now, experts say the field has few viable alternatives to replace the 1-to-10 scale.

Are pain clinical trials stuck in the past?

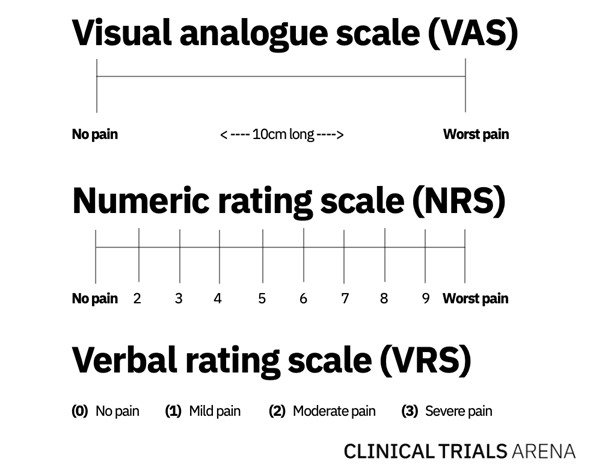

In 1921, scientists M. Hayes and D. Patterson first described a standardised measure for pain in a Psychological Bulletin journal article. Their assessment evolved into the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), which is normally a 10cm line with some variation of “no pain” on the left-hand side and “worst pain” on the right. Patients mark their pain level on the connecting line, which is then translated to a numeric value between one and ten.

MetaHealth-Youth Project metaverse

Researchers subsequently developed the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), which asks patients to rate their pain on a scale of one to 10 using the same outer bounds. A third, albeit much less common, spin-off of VAS is the Verbal Rating Scale (VRS), where patients describe their pain as “none,” “light,” “moderate,” or “severe.”

More than 100 years after Hayes and Patterson published their paper, VAS—along with its close descendants NRS and VRS—are still the standard for clinical trials measuring pain.

Among the three scales, NRS is usually the preferred pain rating scale as previous research suggests it is slightly more sensitive, explains University of Rochester pain researcher Dale Langford, PhD. In general, patients are less likely to misinterpret NRS than VAS.

However, research contrasting these endpoints is not necessarily definitive. “There's a huge amount of data comparing the performance of these pain scales, but almost none of it is actually informative for someone conducting a clinical trial,” Katz says. “It's like dying of thirst on a rowboat in the middle of the ocean.”

Hunt for new pain trial endpoints

In 1988, researcher Nicholas Bellamy validated a multi-dimensional pain endpoint specific to osteoarthritis of the hip and knee, consisting of subscales for pain, stiffness, and physical function. Bellamy’s endpoint, known as WOMAC, is much more sensitive than NRS, prompting its widespread use in clinical trials for osteoarthritis.

Few other indications have followed suit, and NRS remains the standard endpoint for most other fields targeting pain. The reason, Katz says, likely comes down to money.

Developing and validating a new endpoint could take two years and cost $2 million, delaying a drug candidate’s time to market for several years, Katz explains. In an industry beholden to quarterly earnings reports, such delays are often out of the question, he adds.

As one potential solution, Langford is collaborating with the FDA and patients to create a new pain endpoint tailored to specific types of pain. If it gains the FDA’s final approval, Langford says companies “can handpick this endpoint” without any hurdles to applying it in clinical trials. Langford’s team recently re-submitted the paper to the Journal of Pain, which she says should be published soon.

"We're targeting the whole continuum of the pain experience, " says Langford.

The new proposed scale will use a combination of numbers and verbal descriptors, separating acute and chronic forms of pain, Langford explains. Acute pain conditions include pain following surgery, pain following illness or infection, and pain following injury. Meanwhile, chronic pain conditions include lower back pain, post-surgical pain, diabetic peripheral neuropathy, osteoarthritis, and fibromyalgia.

“We’re targeting the whole continuum of the pain experience, and we’re also very specific,” Langford says. “We’re tailoring the instructions to specific pain conditions and recruiting patients with those pain conditions.”

Is the numeric rating scale here to stay?

Although there is support for new primary outcomes for pain, there is not a consensus. Yale University psychologist Robert Kerns, PhD, says that NRS is likely the best measure of pain intensity and should continue to be a primary endpoint in pain studies.

Most patients are comfortable with NRS and agree that pain intensity is a straightforward measure of their subjective experience, Kerns says. In addition, there are thousands of research papers using NRS over the course of several decades, making NRS a familiar comparator for any new studies.

“I’m never into fixing a problem that isn’t broken,” Kerns notes.

However, Langford notes that not all previous trials with NRS are easy to compare and aggregate. Research has shown that differences in labeling—such as describing 10 as the “worst pain” versus the “worst pain imaginable”—can substantially impact how patients interpret and report the scale, she explains. Many trials also use different recall periods—such as “current pain level” or “average pain over the past 24 hours”—and some use 20- or 100-point scales instead of ten.

Nevertheless, experts agree that any pain primary endpoint should be supplemented with a wider-reaching set of secondary endpoints. While Kerns contends NRS should be the primary endpoint, he says secondary endpoints should measure emotional well-being and disease-specific function. Global clinical impressions of pain, which ask patients how they perceive their pain to have changed, can also paint a fuller picture of a patient’s experience with pain, Langford adds.

Improving NRS on the margins

Convinced that NRS has too strong a foothold in pain studies to change, some pain trial researchers are focusing their efforts on improving its sensitivity. One such strategy is running a decentralised clinical trial (DCT) where patients consistently document their real-time NRS scores.

The approach, known as ecological momentary assessment (EMA), has patients regularly recording their pain on an app, explains Northwestern University pain researcher Andrew Vigotsky. Traditionally, pain trials compare a reading of NRS at the beginning of the study with a reading at the end, which removes granularity from patients’ day-to-day experiences. EMA can more sensitively portray a patient’s pain in the context of their day-to-day life, he notes.

Meanwhile, other researchers have developed programs designed to train patients to document NRS scores more accurately. One strategy is to help patients “anchor” the ends of the NRS by standardising what patients perceive as a 0 versus a 10 on the scale, Langford explains.

Another approach is a training module through Analgesic Solutions, which Katz founded and of which is currently the COO. In the FDA-approved training, patients rate the pain intensity of varying levels of stimuli, learning how to document relative changes in intensity.

At first, Katz and his team developed a pre-screening test meant to exclude patients who could not report pain intensity accurately. However, this resulted in around 20% of patients failing screening, which most drug manufacturers deemed too high for a field that often struggles to recruit patients, he notes. In the end, training patients was more cost-effective. “We decided to work around the problem of not having the best pain measures available,” Katz says.

What is pain?

Pain is, at its core, a subjective experience, and science is a long way away from understanding pain intensity in objective terms, says University of Pennsylvania neurologist Dr John Farrar. Brain imaging can show when the nervous system is transmitting signals to different parts of the brain, but it cannot show how that pain impacts a person and daily life, he explains.

Attempting to measure pain objectively through underlying neurological pathways could prove ethically problematic, Kerns adds. This could lead doctors to doubt or discount the pain that patients describe, which is already a concern in the medical community, he notes.

But above all, ongoing efforts to improve subjective measures like NRS, and validate alternative patient-based outcomes, could improve clinical trials while keeping the focus on patients. Each of these strategies can help people better answer the simple yet perplexing question: “How badly does it hurt?”

Main image: Macrovector / Shutterstock.com