Image: Atomwise CEO and co-founder Abraham Heifets

What does Ireland’s tax hike mean for pharma?

Ireland recently agreed to a 15% minimum tax rate. GlobalData explores the implications for the pharmaceutical companies based there.

Dr Judith M. Sills. Credit: Arriello

Dr Eric Caugant. Credit: Arriello

In October, 136 countries signed up to a major reform of the international tax system that will levy multinational companies at a 15% minimum rate from 2023. The agreement, led by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), will raise the rate in 23 jurisdictions that currently have a tax rate lower than 15%, some as low as 0%.

The global pharma industry will be most affected by changes in Ireland, where the rate is currently 12.5%. For many years, Ireland has attracted investment and re-domiciliation by pharma companies and CMOs with a tax rate lower than that of the US and most of Europe.

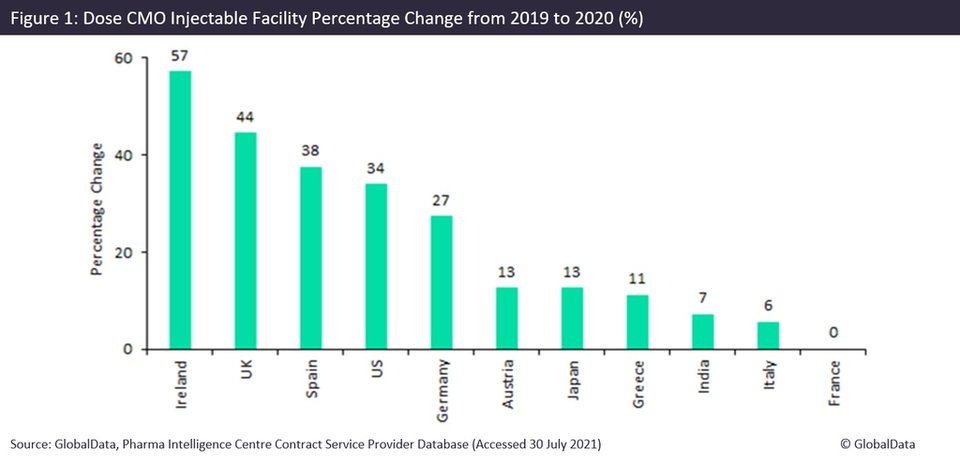

Figure 1, from the GlobalData report ‘Contract Pharmaceutical Dose Manufacturing Industry: Composition, Size, Market Share and Outlook – 2021 (September 2021)’, shows that Ireland is the country that gained the most facilities for contract manufacturing injectable drugs between 2019 and last year (as a percentage change), with the addition of four new facilities.

Besides tax, the UK’s exit from the European Union last January also prompted some companies to move from the UK to Ireland.

Companies with facilities in Ireland

Two dedicated CMOs have facilities in Ireland: PCI Pharma Services (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and Almac (Craigavon, UK). Almac, based in Northern Ireland, opened a site 40 minutes across the border in Dundalk, Ireland, in response to Brexit.

Eighteen excess capacity CMOs have two or more facilities in Ireland, including Merck & Co (Kenilworth, New Jersey) with six sites, Viatris (Canonsburg, Pennsylvania) with five, and Pfizer (New York, New York), Takeda (Tokyo, Japan) and Johnson & Johnson (New Brunswick, New Jersey) with three sites each.

A further 11 dedicated CMOs have their headquarters in Ireland. There is only one public company, Steris (Dublin, Ireland), that has contract manufacturing facilities in Ireland.

Through a series of inversions in the last decade, Steris has lowered its tax bill. The company re-domiciled from the US to the UK in 2014 by acquiring the UK-based company Synergy Health for $1.9bn. It then moved from the UK to Ireland in 2019, citing a combination of Brexit and taxes in an SEC filing: “Steris believes that more than $50m in future US financial benefits supported by tax treaties between the US and the European Union member states will be at risk if the company remains domiciled in the United Kingdom after Brexit.”

In 2016, Pfizer attempted to acquire Irish firm Allergan (Dublin, Ireland) to execute an inversion that would have redomiciled Pfizer in Ireland and reduced its tax, but a change to tax rules under President Obama led the companies to drop the deal.

Shire (Dublin, Ireland) cited tax reasons when it moved from the UK to Ireland during the 2008 financial crash, although its latest owner, Takeda, is restructuring the company so that more profits flow from Ireland to Japan.

What does the tax mean for Ireland and pharma?

The OECD claims the minimum 15% tax rate will redirect more than $125bn of profits from around 100 of the world’s largest multinationals to countries’ coffers. This new rate will apply to companies with revenue above $840m.

Another part of the agreement will re-allocate some taxing rights from companies’ home countries to the markets where they sell drugs and earn profits. This affects companies with global sales of more than $23m.

The tax hike is far from a disaster for pharma companies in Ireland, says Fintan Clancy, partner at the law firm Arthur Cox, adding that pharma multinationals consulted during the process largely considered a rise in rates from 12.5% to 15% to be acceptable.

Despite this, many pharma companies have moved to Ireland because of its tax situation; will the 2.5% hike cause them to move away or stop investing?

“Where would you move to?” asks Clancy, noting that taxes in other popular pharma hubs are higher: the UK’s rate last year was 19% (rising to 25% in 2023), the US’ was 21%, Germany’s was 30% and France’s was 28-32%.

Pharma companies’ location decisions have ‘never been driven solely by tax’, Clancy adds. Office and plant space, the availability of qualified employees and legal protections for intellectual property are also crucial. “If all other things are equal, the tax might be the deciding factor,” he adds.

Moving a business is disruptive and expensive, especially if it involves a manufacturing site, which will require training staff and obtaining regulatory authorisations. Steris’ Irish sites predated its incorporation in Ireland, yet it estimated that its move from the UK cost $10m.

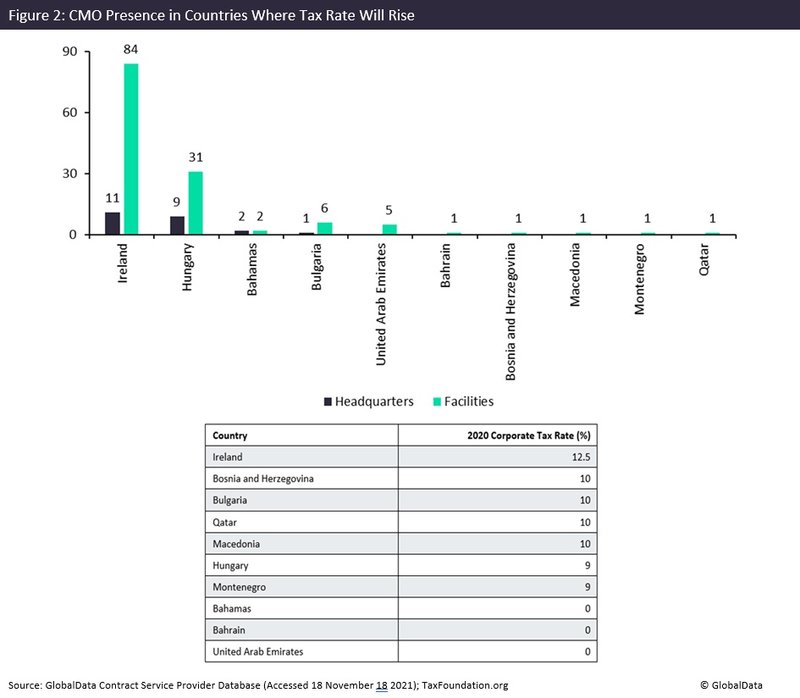

Figure 2 shows the excess capacity and dedicated CMOs with headquarters and/or contract facilities in countries whose tax rate for multinationals will rise in 2023. Ireland will be the most affected, as it has 84 contract manufacturing facilities and 11 CMOs based in the republic.

Inverted companies and subsidiaries

The minimum tax rule will also affect companies based in territories that did not sign up to the 15% rate, such as the Cayman Islands or Singapore, if they have subsidiaries in signatory countries such as the US or China.

“On so-called inverted companies, if you have a parent company in the Cayman Islands or Bermuda and those territories don’t introduce a 15% tax rate, then their subsidiaries – for instance, in the US – will have to pay tax in the US on royalties they are paying to the Cayman or Bermuda parent,” Clancy told us.

“This may mean that these jurisdictions will introduce a 15% tax rate, or perhaps they will stay outside the agreement and accept the consequences.”

Comment from