Insight

Off-the-shelf CAR-T therapy: broadening the reach of precision medicine

Although it seems like a contradiction in terms, creating off-the-shelf versions of precision medicines, such as CAR-T therapies, is increasingly being seen as an answer to manufacturing challenges facing the current autologous approaches. Allie Nawrat explores Celyad’s allogeneic, off-the-shelf CAR-T therapy CYAD101 as a case study of the model’s promise.

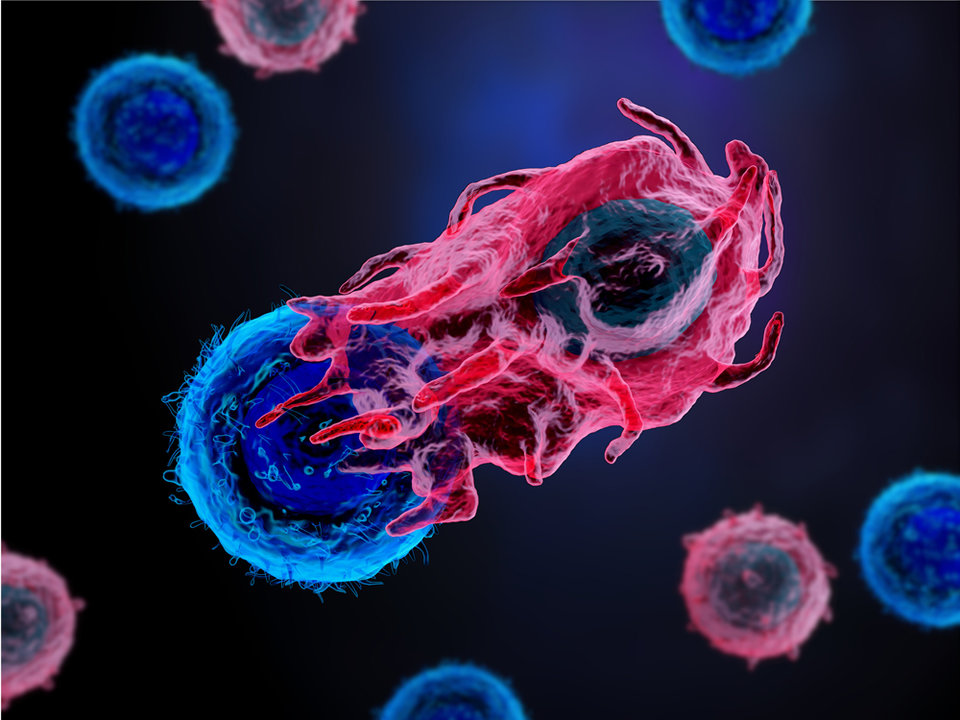

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies, where a patient’s cells can be modified to improve their action against cancer cells, have become central to the emerging field of personalised therapy. Two CAR-T therapies are currently on the market – Novartis’ Kymriah and Gilead’s Yescarta – and many more are in development. As these therapies use the patient’s own T cells, they are known as autologous CAR-T.

Although autologous CAR-T therapies have revolutionised cancer treatment for certain tumour types, they come with huge price tags, primarily due to the long and complex manufacturing process involved in developing a treatment specific to each patient. Novartis, in particular, has experienced significant supply chain delays for Kymriah.

One tactic to overcome the manufacturing challenges in the autologous approaches is to investigate allogeneic manufacturing approaches, where cells from a healthy donor are used to create larger quantities of CAR-T therapies that can be administered to multiple patients. This can create so-called ‘off-the-shelf’ CAR-T therapies, a concept that borrows from trends in stem cell transplants.

One company that is leading the off-the-shelf CAR-T field is US-Belgian biotech firm Celyad. The company’s CEO Filippo Petti notes: “Allogeneic is where we believe the field will eventually go and we want to be leaders there.”

Expanding from autologous approaches

Although originally the company focused on an autologous programme centred around the CYAD01 product – because that was the core of the asset Celyad bought in from Dartmouth University and, as Petti explains, “That’s where the majority of the focus around CAR-T modality has really risen,” – it gradually began to experiment with an allogeneic approach.

This led to the development of a product called CYAD101, which is currently being studied in the Phase I alloSHRINK dose escalation study; this is the sister study to the SHRINK study of autologous CYAD01. These two products are being studied in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC).

Celyad has submitted an investigational new drug application for CYAD101 with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and proof-of-concept for the off-the-shelf approach was achieved in the alloSHRINK study, as announced at the recent Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) conference.

De-personalising precision medicine

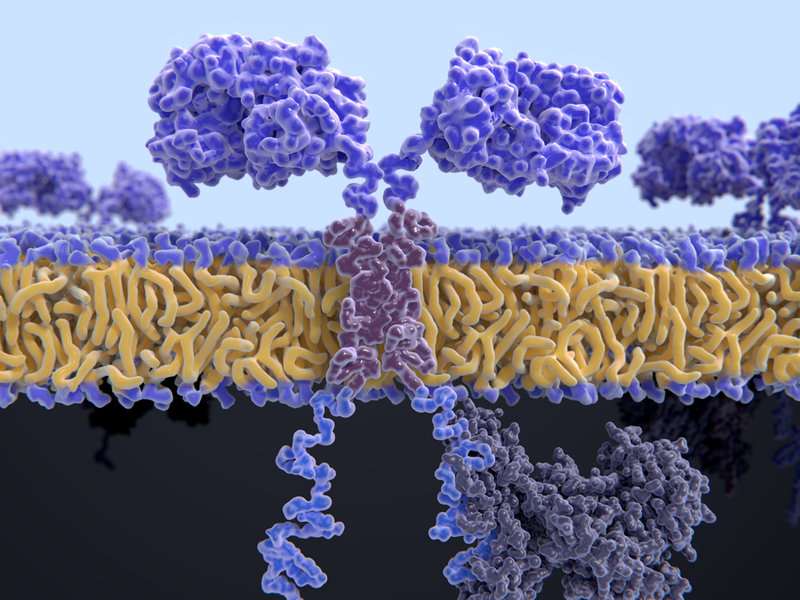

One way to create off-the-shelf CAR-T therapies is using technology to “knock out”, as Petti terms it, or inhibit the T cell receptors (TCR) so donor-derived cells can be given to a patient.

Celyad has adopted a non-gene edited approach to inhibit TCRs called T cell inhibitory molecule (TIM) technology, rather than molecular ‘scissors’ such as CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing approaches. Molecular scissor approaches manipulate the TCR, whereas Petti explains Celyad’s technology “just knocks down the signalling capacity” of the T cells by expressing a peptide to interfere with the signals.

The company is experimenting with a newly bought-in Horizon Discovery technology called short hairpin RNA (shRNA) to interfere with the expression of TCR.

Either of these technologies creates a so-called “all-in-one vector approach”, which Petti and Celyad believe has many benefits against both autologous manufacturing approaches and other allogeneic, gene-edited strategies.

Advantages of allogeneic over autologous approaches

The technology leads to “improved process development for manufacturing due to a single transduction step that allows cell processing to be efficient for the selection of CAR-T,” Petti argues. This creates scalability in manufacturing, an issue that has plagued CAR-T therapies to date.

The entire supply of CYAD101 for the alloSHRINK study – currently consisting of 12 patients – came from one donor. All they did was express their CAR – the NKG2D receptor – inhibit the TCR using proprietary technology and produce large numbers of cells that can be administered via injections into patients.

This compares to autologous approaches, where samples need to be extracted from individual patients. There is a labour-intensive step to separate them out, perform genetic modification, activate them to prepare them for a viral vector, which will be used for administration back into one patient. Therefore, it can take up to a month for one patient to receive a CAR-T therapy.

In addition, Petti believes this approach “limits the number of GMP [good manufacturing practice] elements necessary for manufacturing, as compared to gene-edited approaches, which could help to make manufacturing more cost-effective.”

Urgent need in solid tumours

Refining manufacturing approaches through embracing allogeneic CAR-T therapies is generally important to the long-term utility of personalised therapies, but it is particularly urgent in the field of solid tumours.

Novartis’s Kymriah and Gilead’s Yescarta are both only indicated for specific blood cancers. Petti explains: “There has been more work initially around the haematological indications, in particular [with] targets.”

The reason why blood tumours have been the primary focus of CAR-T therapies to date is because solid tumours pose a significant challenge in drug development. Petti explains this is because rather than focusing on blood cancers, which are easily accessible in the bloodstream, “you are [talking about] trying to invade the tumour microenvironment and work through some of the immunosuppressive conditions around [these solid] tumours.”

However, Ceylad has overcome these challenges and is focusing its CAR-T therapies on solid tumour types, meaning as well as transforming the CAR-T field in terms of off-the-shelf therapies, the company is forging ahead of the competition in broadening out personalised to more oncology indications and patients.

The alloSHRINK and SHRINK studies are both focused on mCRC, which is a solid tumour. To do this, the company explicitly chose NKG2D as its CAR for both CYAD01 and CYAD101, because “it is not focused on one specific target – it actually looks for eight different ligands and targets”, meaning it is effective across various tumour types, both haematological and solid.

Petti states: “Solid tumours…are eight to ten times more common [than blood cancers], so if we're going to go out and try to treat 150,000 patients with mCRC diagnosed in the US every year, from a manufacturing standpoint, it becomes a different dynamic.

“For solid tumours, we do believe that allogeneic, off-the-shelf, CAR-T therapy becomes the long-term prospect.”

Clinical equivalence to autologous

Although it is incredibly important that allogeneic CAR-T therapies are broadening the reach of personalised medicine, this only matters if the therapies are actually effective in patients.

One of the major concerns with allogeneic approaches is combating graft-versus-host disease, which is a common complication of receiving tissue from another individual. However, Celyad announced at SITC that there was an absence of this complication in the alloSHRINK study of 12 patients when administered with Folfox chemotherapy – CYAD101 was generally well tolerated by the trial participants. Petti also explains that chemotherapy is very important to prevent CYAD101 “causing stress in healthy tissue, because our CAR-T attacks stress [through the NKG2D target].”

As a result of this promising data, Celyad has concluded that the TIM tech is effective at inhibiting TCR and that following chemotherapy, there was similar efficacy to their autologous CYAD01 therapy. These interim results showed that 50% experienced a reduction in tumour burden and five of the 12 achieved a stable disease status over at least three months.

The future of Celyad’s off-the-shelf CAR-T

In addition to continuing the clinical development of CYAD101 in mCRC and hopefully bringing it to market, Petti says the company is looking into other allogeneic technologies and potentially further solid tumour indications.

He notes that although the TIM technology is particularly effective with the NKG2D CAR, “we are looking for a broader approach and a broader platform,” hence Celyad’s purchase of the shRNA technology.

“As we go over into 2020, we hope to usher forward shRNA-based off-the-shelf approaches into the clinic, and then we’ll look to prove out that technology on well-established [CAR-T] targets, like BCMA and CD19.”