Feature

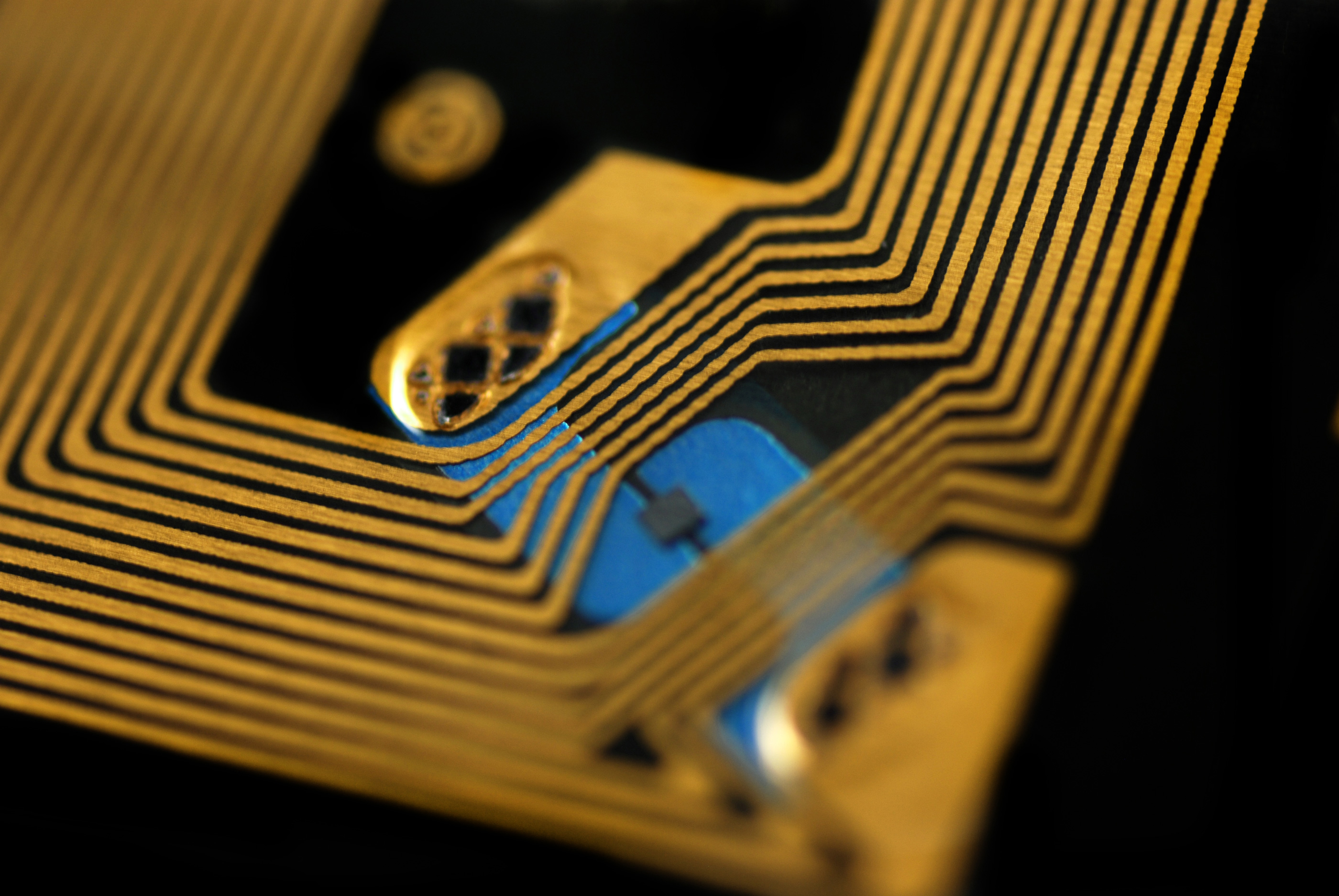

Is RFID the future of smart labelling?

Cloud-based registries that use radio frequency identification (RFID) offer an alternative to track drug supply. Sally Turner reports.

Credit: Bert van Dijk/Getty images.

The pharmaceutical industry began using radio frequency identification (RFID) tags in the early 2000s. Pfizer was the first to use the tech, adding RFID tags to track a Viagra (sildenafil) shipment circa 2006. Various uses soon became apparent including those for supply chain management, anti-counterfeiting, and to improve patient safety.

As computing has developed in the past decade, so has the potential to store and use information in the cloud. In recent times, suppliers have also chosen other systems that rely on blockchain and sensors to track drug supply and reduce the influx of counterfeit drugs.

Why has the use of RFID fluctuated over the past decade?

“First has been the cost”, says Franck Germain, VP marketing at Linxens, a global technology company that manufactures electronic components for security and identification, including RFID antennas and inlays. “Twenty years ago, the cost of implementing RFID tags and the ecosystem (software) was much more expensive than today. Solutions were also much more complex to implement [then], whereas today there are a lot of companies in the market offering multiple solutions.”

He adds that in the early 2000s there were no set standards for RFID in the pharma industry, so the compatibility between systems was not guaranteed. There were also, and still are, some privacy concerns about what exactly is tracked and how data is used.

Twenty years ago, the cost of implementing RFID tags and the ecosystem (software) was much more expensive than today.

Franck Germain, VP marketing at Linxens

In recent times, various global administrators have issued regulatory standards. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has provided guidance for the use of RFID in the drug supply chain and to standardise the data format. In the US Drug Quality and Security Act (DSCSA), the FDA mandates that manufacturers and trading partners should have full interoperable electronic track and trace systems in place by November 2023. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has produced similar recommendations, but with a focus on using RFID tags to track the movement of drugs through the supply chain, and instructed companies to implement appropriate security measures to protect patient privacy and prevent counterfeiting.

Cloud-based registries and RFID – a value-add?

“Every RFID vendor has their own version of a cloud-based system, so it is up to the customer to decide what features and benefits are important to them,” says Gwen Volpe, senior director, Medication Technology, Fresenius Kabi USA. Fresenius Kabi is a global healthcare company specialising in medicines and technologies for infusion, transfusion and clinical nutrition.

She continues: “Whether a vendor has a cloud-based registry, system, or database, it’s crucial that pharmaceutical companies who pre-tag for RFID systems use accepted, recognized global standards to encode drug data so products can be read by any system, just like the GS1 barcodes that are on every pharmaceutical product today.”

In August of 2022, Fresenius Kabi announced a three-year plan to add GS1 Data Matrix barcodes, also known as 2D barcodes, to its US pharmaceutical portfolio. The aim was to streamline workflows in healthcare facilities by reducing error-prone manual data entry for every customer. In 2020, Fresenius Kabi introduced their first RFID-enabled medication, Diprivan +RFID. One of the primary goals for their +RFID portfolio was to ensure that their RFID-enabled products work for all customers no matter what type of RFID reading system they use.

“That is where GS1 standards come in,” says Volpe. “Hospital clinicians should never have to decide whether our +RFID products are compatible; medications should work effortlessly in whatever system a hospital wants to purchase. Using GS1 standards allows us to do just that.”

Germain adds that cloud-based registries offer different value-adds such as supply-chain visibility and improved efficiency. The use of the cloud allows better data management in centralised places, enabling pharma companies to provide a higher level of security for stored data while ensuring it is accessible when needed. With the centralization of data storage, it also offers regulatory bodies such as the FDA an easier way to track and monitor practices and safety.

Credit: SHutterstock/ Montri Nipitvittaya

Cloud-based challenges

The challenges of using cloud-based tech relate in part to what slowed the deployment of RFID initially. “Data standardisation and interoperability of systems is not ensured and can create challenges through the entire logistics chain,” suggests Germain. “Security can also be a challenge, especially when several systems are involved and need to work together. The more systems and data sharing exist, the more the risk of data breaches is important.”

In this backdrop, blockchain is an emerging alternative. “Suppliers implement more and more blockchain and sensors mainly for security reasons,” explains Germain. “Blockchain technology provides an immutable and tamper-proof record of transactions, which makes it very hard for counterfeiting. In addition, sensors can offer a better track of the physical location for a pharma product, and both are compatible with existing systems in most cases.”

What lies ahead for RFID and smart labelling

According to a report by Future Market Insights, the global RFID in pharmaceuticals market was worth more than $1.4 bn in 2022 and is predicted to grow at an impressive compound annual growth rate of 7.9% to top $ 2.2 bn by 2028. The analysis suggests that the developing need for efficient supply chain management is expected to support demand growth of RFID in pharmaceuticals over the decade.

Volpe agrees that “the future is bright” for smart technologies that identify, monitor, and track medications through the supply chain.

“However, to make it all work – regardless of technology – we need trusted, reliable, global standards that provide a common digital language to communicate that data across the supply chain’” she adds.

Moreover, other regulatory factors still need to be finalized. Volpe adds that the FDA has not yet decided on the overall encoding standard for RFID as it has with barcodes.

“This means that pharma companies could be forced to make decisions that may limit their ability to sell their product to all of their RFID customers,” she says. “Using the same type of open, global, standard like we do for barcodes makes sense for the pharma industry, so that a customer can use an RFID-enabled pharmaceutical product from any company at any time.”

RFID is an important facet of smart labelling and its evolution, but not the only one. “Other technologies such as near-field communication and Bluetooth Low Energy are viable complementary alternatives with different advantages,” advises Germain. “With more and more devices becoming connected, cloud-based platforms can help to integrate and manage data from these devices. They enable real-time data sharing, collaboration, and analytics across the supply chain, bringing more security and efficiency as well as confidence into our pharma products.”

So, moving forward, it is not about one single technology but how all of them combine and work together to increase efficiency across the industry.

Credit: Shutterstock/Tyler Olson