FDA Approval

FDA shows unease about marketing approval applications based on single-country trials

A recent regulatory call by the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) has raised questions about the agency’s policy on approving drugs based on single-country trials. Milena Izmirlieva writes about the implications of the sintilimab decision.

Alisdair Lackie

In 2019, the director of the US FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, Richard Pazdur, suggested that the approval pathway for PD-1 inhibitors supported primarily by Chinese data would be relatively straightforward. However, he appears to have revised this stance as the FDA has adopted a critical approach to Innovent Biologics and Eli Lilly’s application to market sintilimab as a first-line treatment for non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

While some of the FDA’s concerns are focused on sintilimab’s Biologics License Application (BLA), they may also indicate broader regulatory concerns about the transferability of clinical data from a single foreign country to the US setting.

Concerns raised about sintilimab’s application

An FDA briefing document released ahead of the FDA’s Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) meeting on sintilimab, which occurred on February 10, 2022, outlined three requirements that had to be met before the FDA would consider an approval based solely on single-country foreign data. They are as follows:

- The foreign data must be applicable to the US population and US medical practices.

- The studies have been performed by clinical investigators of recognized competence.

- The FDA is able to validate the data through an on-site inspection or other appropriate means.

Based on these requirements, sintilimab’s ORIENT-11 data was found to be lacking. Clinical sites used in the trial had not had full FDA inspections, while trial investigators had had “limited interactions with the FDA,” thereby restricting the agency’s ability to assess their capabilities. Furthermore, the comparator arm in the study—chemotherapy—did not reflect the standard of care in the US. Checkpoint inhibitors have been available as frontline treatments for metastatic NSCLC since 2017, but these were not approved in China at the time of the ORIENT-11 trial initiation.

The Briefing Document also criticized the fact that ORIENT-11 had progression-free survival (PFS) as the primary endpoint instead of overall survival (OS), which “remains the preferred endpoint when it can be reasonably assessed.” The Briefing Document added that “Given that there are multiple approved agents with OS advantage formally demonstrated with statistical significance, flexibility regarding applicability of results from ORIENT-11 is not indicated or favorable for US patients.”

The ODAC agreed with the points raised in the Briefing Document, voting with a 14-1 majority that sintilimab could not be approved based on the clinical data and that additional clinical trials will be required to secure marketing authorization in the US.

International guidelines

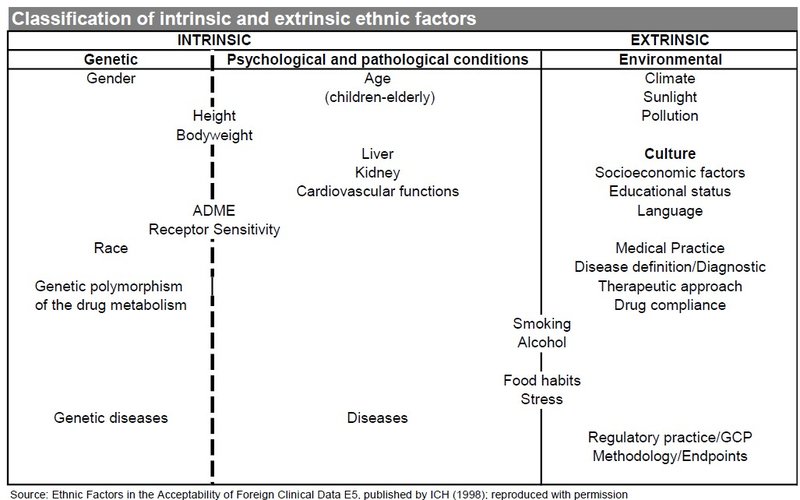

One key guideline that the FDA and other regulators take into account when judging trial data is the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use’s (ICH’s) “E5 Ethnic Factors in the Acceptability of Foreign Clinical Data,” which was published in February 1998 and implemented by the FDA in June 1998. The E5 guidelines consider intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including genetic, cultural, and environmental characteristics in determining whether data for one country can be extrapolated to another.

A separate E17 guideline, published by the ICH in November 2017 and entitled “General Principles for Planning and Design of Multi-Regional Clinical Trials E17,” recommends the inclusion of patients from diverse backgrounds, taking into account both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, to allow the generation of data that is acceptable to multiple regulatory agencies.

The Briefing Document suggested that while Innovent cited the CFR and the E5 guideline in its BLA for sintilimab, it had neglected to reference the E17 guideline.

Implications for other products in development

Some of the reasons specified in the ODAC rejection are specific to the sintilimab BLA, but drug developers should be aware of how they may affect future applications.

The choice of an appropriate comparator, in line with current clinical practice, is particularly important.

Despite the clear preference for multi-regional clinical trials (MRCTs) mentioned by the FDA Briefing Document for sintilimab, the ICH E17 guideline makes provisions for the acceptance of single-country trial data in specific cases, “such as in the evaluation of drugs to treat or prevent a disease that is prevalent in a single region (e.g., anti-malarial drugs, vaccines specific to local epidemics, or antibiotics for region-specific strains).” Drug developers can certainly take advantage of that option.

In practical terms, the FDA has also been willing to show flexibility in cases where there is a genuine unmet need for a new treatment or new indication. For example, the FDA granted priority review to toripalimab, which was originally developed by the Chinese company Junshi Biosciences and the US company Coherus Biosciences gained the US and Canada rights in 2021. The FDA granted the priority review despite the fact that the BLA was supported solely by Chinese trials. This decision was likely influenced by the fact that no other immunotherapies have been approved in the US for nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Thus, there will be opportunities for other products with single-country trial data to secure FDA approval, but decisions will be based on the specific characteristics of the product, the rationale for conducting a single-country trial, the level of unmet need, the transferability of clinical findings to a US setting, and, crucially, the selection of an appropriate comparator.