company insight

Your One-Stop Solution to Powder Flow Issues

Achieving compliance with local requirements can be a tough deal and an unexpected challenge sometimes

Your Problem:

You are a production engineer at Company A1B2 – a pharmaceutical outsourcing company that packages drugs for several major pharmaceutical manufacturers in the American northeast. You are one of a team of six senior staff who each coordinate several packing jobs annually. Major Pharma is one of your largest accounts. You run two batches annually of their antidepressant drug – each batch valued at about USD $8,000,000. Your most recent packaging job was a revised formula of Major Pharma's antidepressant drug. The revision in formulation resulted in a significantly finer powder than previously received for packaging. QC personnel on this last batch discarded a record 37% of product due to poor quality. Standard discard from a tablet run is 17%. You realize that the 17% is high (you would really prefer to get that down to 3%-5%), but you can still run a good profit margin at 17% loss.

You have this information from your QC personnel: Content uniformity of the tablets was off: high API content in tablets from the beginning of the run account for 20% of the loss and low API content in tablets from the end of the run account for 17% of the loss.

You have this information from your production manager: The process is shut down for this drug because it cannot be packaged (tableted) with acceptable quality in sufficient quantity to satisfy Major Pharma.

You are EXTREMELY concerned about losing this major account. You designed this system several years ago and it has always worked with this drug. However, as the engineer responsible for the process design, this significant failure goes directly to your credibility and future sales with Major Pharma. You are not sure what is causing the significant variation in API concentration throughout the batch run. Additionally, you know that you cannot change the product. You can, however adjust the process by switching out blenders, storage and transfer hoppers, and/or feed systems from the several pieces of process equipment in your stock...if you could figure out the root cause of the product quality problem.

If the powder blend is too cohesive due to the finer particle size, then it is likely arching in the tablet press.

We Will Help You Solve Your Problem:

We would begin by running a set of material property tests on your new pharmaceutical powder blend. We would quantify bulk strength, cohesiveness, true density, bulk density, gas permeability, wall friction angle, angle of repose, and segregation potential for each component in the blend, as well as for the blend itself.

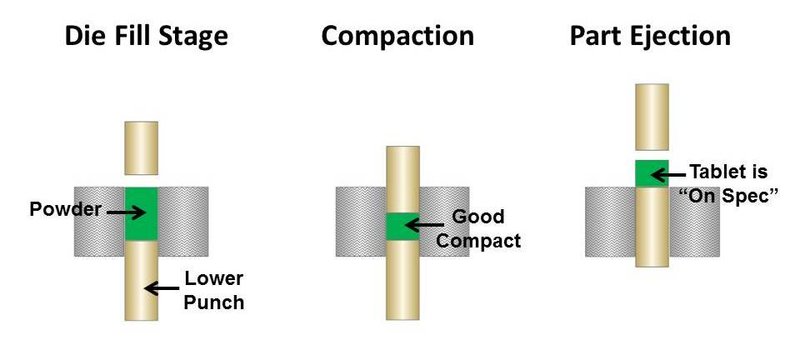

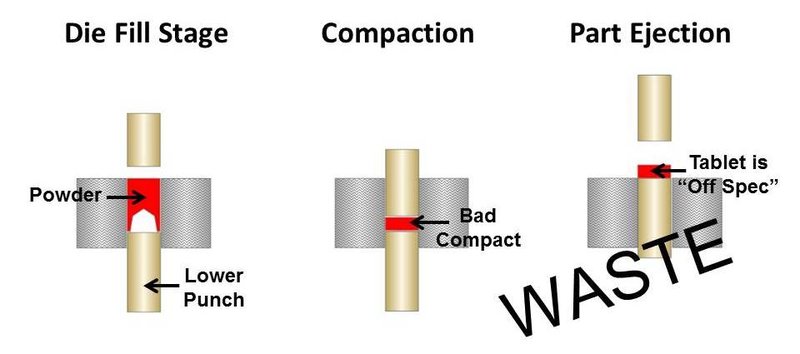

If the powder blend is too cohesive due to the finer particle size, then it is likely arching in the tablet press. This will always result in irregular tablet size and density and could be a cause of the off-specification product. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate what can happen in a tablet press when fine powder blends arch across the press orifice.

Figure 1. Good pill compaction

Figure 2. Poor pill compaction

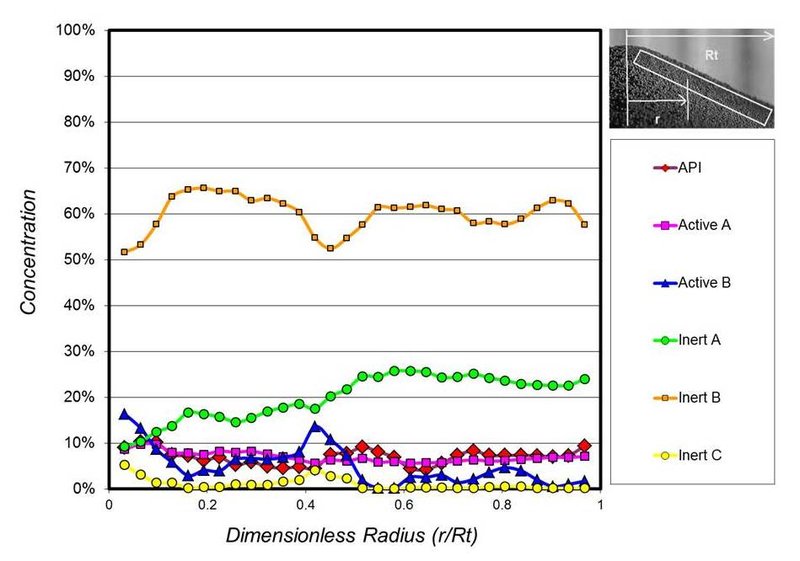

If the increased fine particles are sifting through larger-sized particles in the blend, then the result would be segregation (separation) of the blend components during processing. Figure 3 shows the measured concentration of a 6-component heart-healthy drug as it forms a pile in the process hopper. A completely straight line would indicate no segregation. An erratic line indicates a level of segregation. Again, this particle segregation will generally result in off-specification product unless the process is designed to re-blend the material at key locations.

Figure 3. Measured concentration for a 6-component heart-healthy drug as it forms a pile in the process hopper

With this measured data we can determine the cause of your off-specification product – whether the problem is powder arching in the press, separating in the system, or some combination of both. Then, using our proprietary analysis tools, the measured data and a schematic of the existing system, and our extensive experience in the industry, we would provide you with conceptual retro-fit design recommendations for changes to the existing system and system operations which would eliminate or significantly mitigate the packaging issues to within your acceptable parameters. As a matter of policy, we always attempt to use as much of your existing system as possible. Finally, we do realize that the design process can be iterative, therefore, we would work with your personnel to assure that the final design adhere to the necessary parameters to meet Company A1B2’s production goal.

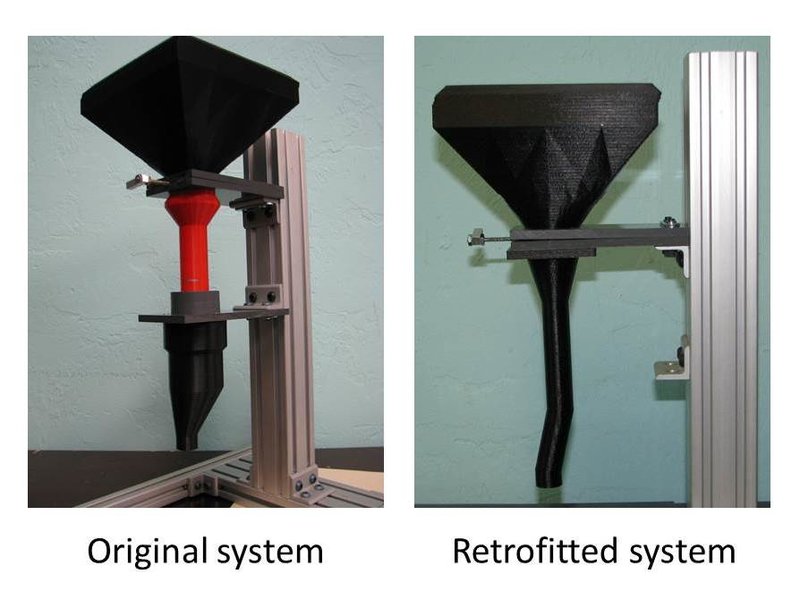

Finally, using 3D printer technology, we can provide a scale-model of the recommended process modifications so you can test the theory. Figure 4 shows before and after models of a feed system used to prevent segregation and arching.

Figure 4. 1/6 scale models using 3D printer technology