Comment

Minimal impact expected for first ten drugs released for Medicare price negotiation

The Inflation Reduction Act aims to generate $25bn in drug cost savings and reduce Part D out-of-pocket (OOP) costs for Medicare beneficiaries, writes Cyrus Fan.

The companies from the selected drugs will have to sign an agreement with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to participate in drug price negotiations by 1 October 2023. Credit: Shutterstock/ John Blottman

The Biden Administration has released the highly anticipated list of ten drugs selected for Medicare price negotiations under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The drugs were selected based on gross Medicare Part D spending from June 2022 to May 2023 and total more than $50bn in Medicare spending, making up 20% of the Medicare program’s pharmacy drug costs over a one-year period. The highly controversial Inflation Reduction Act aims to generate $25bn in drug cost savings for the US Government over the next eight years and reduce Part D out-of-pocket (OOP) costs for Medicare beneficiaries.

The companies of the selected drugs will have to sign an agreement with US's Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to participate in drug price negotiations by 1 October 2023. Failure to do so may mean the companies will face steep tax penalties or even risk losing access to Medicare and Medicaid coverage entirely. The CMS expects pharma companies to provide confidential information on new data points to help determine the initial maximum fair price by 2 October.

The extra data includes R&D costs and the extent to which these costs have been recouped, federal financial support, and data on revenue and sales volume. Pharma companies are to communicate with the CMS and will each likely provide a compelling argument on the economic analysis around their respective products. Other factors that the CMS will consider include the drug’s clinical benefit, comparative effectiveness data, unmet medical needs, and the drug’s impact on specific populations.

Credit: Getty Images/ Halfpoint Images

Further down the line, the CMS must reveal the initial offer of a maximum fair price, with justifications, to each company by February 1, 2024, and each company will have 30 days to respond to the provisional price. Current estimates on the discounted price from the CMS range from 25% off a drugs list price to 60%. The CMS will publish the agreed-upon negotiated prices for the selected drugs by 1 September 2024 to take effect on 1 January 2026.

The drugs that were selected are some of the most used Medicare drugs to treat chronic conditions and are key products for the pharma companies involved. The list of drugs made up over $50bn in Medicare Part D spending during the selected time period, and Medicare enrollees taking the ten drugs paid $3.4bn in OOP costs in 2022. The reduced OOP spending from these price negotiations could lead to higher compliance to therapy.

The list is mostly unsurprising but contains fewer cancer drugs than what most industry experts had predicted. Some drugs may have been left out due to decreased utilisation over the past year. Drugs that were expected to be chosen could still be picked in future years. Two surprising additions to the list were Janssen’s Stelara (ustekinumab), which is due to have biosimilars launched by 2025, and Novo Nordisk’s Fiasp/Novolog (insulin aspart), which already has a $35 insulin price cap for Medicare beneficiaries. Notably, some of the selected drugs are also close to facing generic/biosimilar competition, either before or very soon after the negotiated prices are set to occur. Therefore, the commercial impact could likely be minimal for some of the drugs when the negotiated prices are enforced in 2026.

Additionally, if generic/biosimilar competition enters before 2026, it is possible that the CMS may drop some of the drugs off the list. Under current Inflation Reduction Act rules, drugs that have generic or biosimilar competitors do not qualify for government price negotiations and the CMS could cancel negotiations if cheaper competition enters the market. Stelara has signed multiple deals with biosimilar developers to launch biosimilar competition on 1 January 2025, although it would be up to the CMS to decide what counts as competition.

Current estimates on the discounted price from the CMS range from 25% off a drugs list price to 60%.

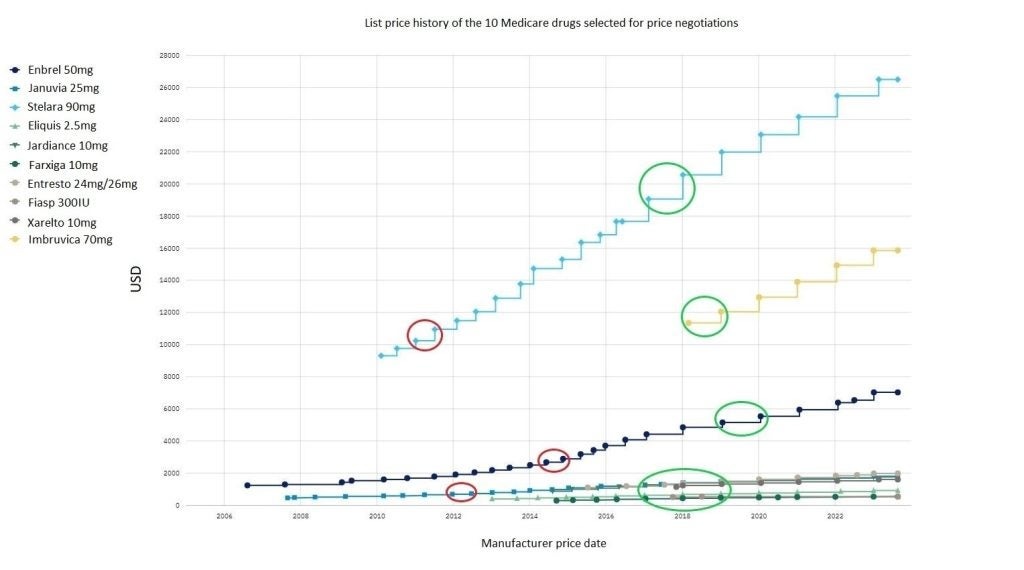

Using data from POLI, we estimated the 25% and 60% price cuts for each of the ten drugs and marked these on the price history graph, historically demonstrating what year the price would equate to. Overall, nearly all drugs with a 25% discount would still be higher than their launch price. For example, Stelara’s current price was $26,517 and with a 25% discount this would be $19,887.75, which was its price around 2017-18. With a 60% discount, Stelara was $10,606.80, which was approximately equivalent to its price in 2011. When Fiasp was discounted, the price at 25% or 60% was lower than its launch price and could not be marked. Some drugs with the 60% discount also could not be marked as it was lower than its launch price. Six drugs all had similar price reductions with a 25% cut and prices equated to the years between 2017-2019, as shown towards the bottom of the graph.

Figure 1: List price history of the ten Medicare drugs selected for price negotiations: Red circles represent a 60% discount to the current list price and green circles represent a 25% discount to the current list price. The possible discounted prices for some drugs could not be marked due to being lower than launch price. Januvia, Eliquis, Jardiance, Farxiga, Entresto, and Xarelto were marked all with a similar price date at 25% discount.

As expected, the pharmaceutical industry and industry advocates have continued to react negatively and have criticized the list. Industry advocates continue to point out that the Medicare drug price program will lead to reduced innovation, result in less investment in small molecule drug development, and affect patient access. Many pharma companies are worried about the fairness of the drug selection decision and argue that Medicare’s gross spending does not take into account rebates, discounts, and fees paid to prescription drug insurance plans. Additionally, the pharma industry argues that patients already have access to the selected drugs at significant rebates and discounts with a relatively low OOP expense. Pharma companies have also pointed out the effects that the Inflation Reduction Act has already caused, including rethinking their pipelines to contain fewer small molecule drugs and changing launch strategies to reach peak sales as quickly as possible.

Currently, the Biden Administration is facing multiple lawsuits launched by pharma companies and industry advocates, and the pharma industry will continue to fight the US government in an attempt to delay the process. The lawsuits all make similar claims that the Inflation Reduction Act violates the US Constitution. Nearly every pharma company that made the list has launched a lawsuit against the Biden Administration, and more are likely to come. This includes lawsuits from companies whose products did not make the list this time, out of fear of being selected for price negotiations in future years. With the increasing number of lawsuits, the cases will likely head to the US Supreme Court for judgment. The Biden Administration has continually commented that it remains confident of its ability to prevail in the cases seeking to derail the Inflation Reduction Act and believes the law is on its side.