TAX LAWS

A cloudy day in paradise for pharma tax havens in Cayman Islands & Bermuda?

A recent international agreement to harmonize tax rates may impact pharma companies headquartered in jurisdictions long considered tax havens. Manasi Vaidya and Fiona Barry report that this deal evokes mixed views on the extent of its real-world impact.

Arecent international agreement to harmonize tax rates evokes mixed views on the extent of the real-world impact for pharma companies headquartered in jurisdictions long considered tax havens.

As of November, 137 countries and jurisdictions have agreed to institute a minimum 15% tax rate for multinational enterprises. The deal facilitated by Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is being presented as a “Two-Pillar solution” to harmonize tax rates internationally and will go into effect in 2023.

Notably, the OECD deal includes territories like Cayman Islands, Bermuda, and Isle of Man, which have very low or 0% tax rates, giving a financial incentive for pharma companies to be incorporated there. If implemented as intended, a global minimum tax rate would dull the financial benefits to pharma companies being incorporated in these regions. However, experts say it remains unclear if these jurisdictions, which have long been considered tax havens, will in fact institute the higher tax rate and whether it will be levied on pharma companies.

Other signatories include the US, EU, the UK and Ireland, which could also have implications for pharma given the multinationals incorporated there.

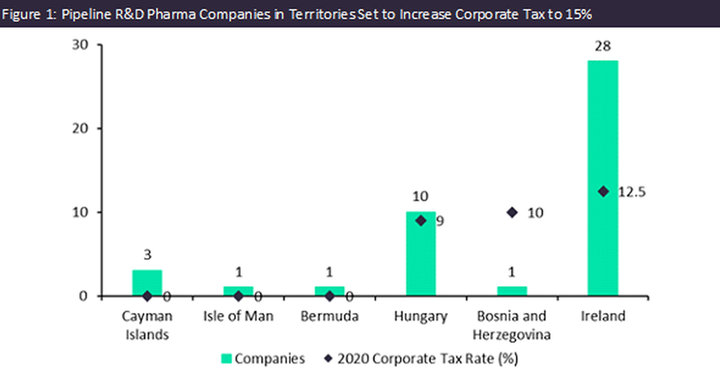

The countries and territories in Figure 1 are all signatories to the OECD agreement, and also currently tax companies below 15%. The lowest tax rates are in Isle of Man, Bermuda, and Cayman Islands, which currently have no corporate tax. They also lack significant research and manufacturing, so companies domiciled here will be reliant on offshore facilities, either in-house or belonging to service providers.

Companies in these regions include Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals, which is headquartered in Bermuda, and is developing the biologic mavrilimumab for COVID-19 and other indications. Altogether, pipeline companies in these six low-tax regions are working on ten COVID-19 pharmaceuticals, including two stem cell therapies from Orbsen Therapeutics (Galway, Ireland) and a vaccine from Cellnutrition Health (Galway, Ireland). Other companies include the oncology-focused companies Coherent Biopharma and OnCusp Therapeutics, which are headquartered in Cayman Islands.

Bumpy rollout for higher tax rate

While the OECD agreement provides a broad outline, it remains to be seen whether all the territories have an incentive to implement the minimum tax rate, said Michel Devereaux, director of the Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation, UK. Reuven Avi-Yonah, Director, International Tax LLM Program, University of Michigan, was skeptical that all 137 signatories would go ahead with the deal, especially the low-tax jurisdictions.

There is precedence for tax havens not following through with such treaties, Avi-Yonah said, referring to the US Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) of 2010. FATCA requires foreign financial institutions and certain other entities to report the foreign assets held by their US account holders or be subject to withholding (where the employer pays tax directly from an employee’s wages to the government). While FATCA dealt mainly with individuals instead of companies, it has not worked to make US individuals report assets in certain foreign jurisdictions like Cayman Islands or Bermuda, as evidenced by leaks such as the 2016 Panama Papers, Avi-Yonah said.

However, it is a different story among countries in the EU, which is fully committed to implementing this minimum 15% tax rate in a legally binding way, Avi-Yonah and Fintan Clancy, partner at the law firm Arthur Cox, agreed. While the European Commission is pushing for this deal, it remains to be seen whether the US Congress or other large countries like the UK, which is trying to attract pharma companies, will have an incentive to go ahead with it, Devereaux said.

R&D and IP Incentives

If the 15% minimum tax rate were to be introduced, the incentive for pharma companies to shift profits to former tax havens is going to be much reduced, Devereaux said. However, those countries could bring in alternative financial incentives to retain pharma companies. “If you were to be a cynical tax haven, you might bring in a 15% tax rate, but you could give a grant of 15%—for example, to companies employing people in your country—that falls outside the tax rules…So you might see regions bring in grants that track the tax they bring in,” Clancy said. While EU companies are limited by “state aid” rules on non-tax incentives that they can offer, the UK and its territories, including Cayman and Bermuda, are not. As such, they could offer pharma companies greater R&D and intellectual property (IP) grants and subsidies.

IP is an important component of pharma companies’ tax strategies, and one that another section of the OECD agreement seeks to address. While 0% tax jurisdictions offer no significant research facilities, pharma companies have long found it attractive to transfer patents to such locations. Even when companies are not headquartered in tax havens, they can still lower their tax bills by moving their patents to these regions. This allows them to pay lower or no tax on royalties obtained on revenues generated from that IP. Pharma companies have been quite good at divorcing the location where they do R&D and where they have ownership of the resulting products, Devereaux said.

For example, as per news reports in 2016, Gilead Sciences was said to have transferred some of its patents on Hepatitis C drugs to Ireland, which allowed it to be subject to a lower tax rate on the sales of those drugs, even though a lot of its R&D was subsidized by the US federal government.

The OECD agreement may change this. Pillar One of the deal re-allocates some taxing rights to the markets where products are sold, regardless of whether the firm has a physical presence there. Pharma profits would first be subject to taxation by the “source” country, where the drugs are sold and profits are generated, then the remaining profit would be transmitted to the “resident” country, where the company is domiciled, for instance, the Cayman Islands, explained Young Ran Kim, Associate professor of Law, University of Utah. Pillar Two pertains to setting the global minimum corporate tax rate set at 15%. If the source country applies anything less than the minimum 15% tax rate, then the resident country would still have to impose the remainder to guarantee a total imposition of 15% corporate tax, she added.

In practice, this means that some of the profit will now be taxed in the country where the product is sold, as opposed to the country in which the innovation occurred, Clancy said. “Both manufacturing and R&D companies will pay more tax in the sales jurisdictions,” he said.

This mechanism means that, even if some territories do not implement the global minimum tax, as long as Group of Twenty (G20) countries implement a minimum 15% tax in their domestic legislation, this may capture the majority of the revenue that has been avoided so far, said Kim. On the other hand, the reallocation of profits section of the OECD agreement only applies to companies with global sales above EUR 20B ($22.6B). It is unlikely to impact early pipeline-stage companies which lack taxable income until their drugs are marketed, Avi-Yonah pointed out.

Source: GlobalData Drugs database (Accessed: December 10, 2021) ©GlobalData

Notes: Pipeline (Discovery to Pre-Registration phase) innovator companies without marketed drugs, excludes entity types: institution, government, subsidiary, joint venture