I

n terms of its research credentials, Canada’s life sciences industry has always punched above its weight. Home to less than 0.5% of the world’s population, the country produces 5% of the world’s research publications, and has a citation rate among the top six nations globally. It also boasts a preeminent medical centre, the University of Toronto, which produces the most peer-reviewed research papers in the world.

Despite its research nous, however, Canada has often struggled to convert its discoveries into commercial products. While the country ranks 15th on the World Intellectual Property Organization’s ‘Global Innovation Index’, it is only 57th in terms of intellectual property (IP) efficiency (i.e., turning IP into economic activity).

What’s more, it is the only major pharmaceutical market in the world without an anchor company. The majority of promising Canadian startups, rather than being scaled up within Canada, get acquired by entities elsewhere.

“Canada is the home to a research powerhouse, and the data are really clear on that front,” says Gordon McCauley, president and CEO of Canada’s Centre for Drug Research and Development (CDRD). “We have substantive public investment in life sciences and a highly entrepreneurial culture, and we lead the world in starting companies. The challenge is to help that research base develop into a sustainable commercial industry.”

Gordon McCauley, president and CEO of the Centre for Drug Research and Development

Accelerating research with strategic partnerships

The CDRD was established to meet that challenge. Since it was founded in 2007, it has been working to accelerate Canadian research, partnering with research organisations to develop and commercialise their discoveries. Its focus is threefold: spinning out companies of scale; helping existing companies scale up; and training life sciences personnel, both on the science and business side.

“A bunch of groups came together – the federal government, the British Colombia provincial government and industry – to set up a unique structure,” says McCauley. “We have 40,000ft of purpose-built laboratories filled with 100 commercially-trained personnel, and our partners have committed significant funding.”

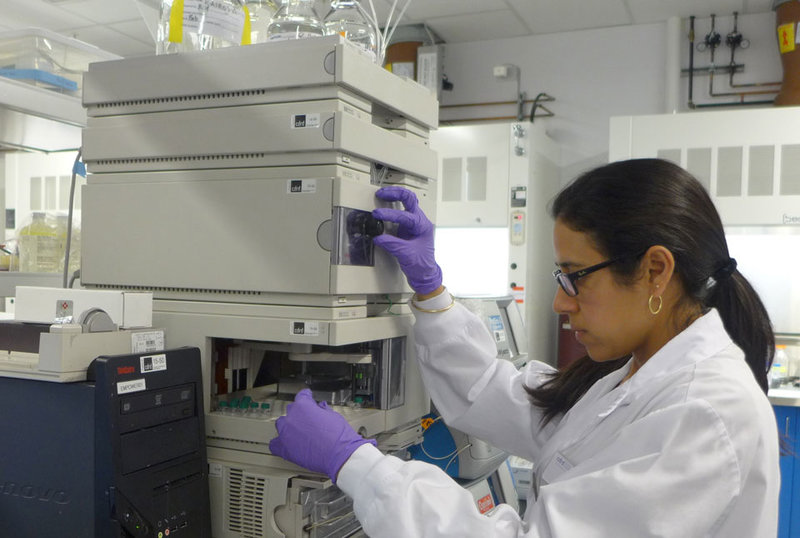

The team works to source new discoveries with genuine commercial potential

Today, the centre maintains strategic partnerships with over 50 universities, 26 Canadian health sciences SMEs, eight translational research centres, six major pharma companies, and three patient-focused foundations. Through harnessing this network, the team works to source new discoveries with genuine commercial potential.

“We spend a lot of energy foresighting – trying to understand where we see science and industry and investors going over the next five to ten years,” says McCauley. “That’s a really important exercise for us, because we need to stay current with industry developments. But what’s really interesting is that, regardless of the developments we see, it’s typically the same four things that matter.”

Image courtesy of the Centre for Drug Research and Development

Finding the right technology

The first and most crucial question relates to the science itself – is this a new discovery, a novel target, or a new way of understanding biological systems? The second question is whether it has commercialisation potential, and is differentiated from products already on the market.

The third criterion is having a clear understanding of the pathway forward, both in terms of clinical development and commercialisation.

“This is one of those things that people often just assume follows with novel discoveries but it’s not always the case – you really have to spend a lot of energy making sure you understand those pathways effectively,” say McCauley.

The fourth is whether there may be an opportunity to build an anchor company around the technology. While the first three criteria are critical, McCauley says the fourth is just a ‘nice-to-have’.

“Our objective is to drive the construction of a sustainable life sciences commercial industry with multiple anchor companies,” he says. “That’s why we spend so much energy focused on spinning out companies of scale.”

Antimicrobial resistance is a very significant global problem

While the CDRD is reasonably agnostic when it comes to therapeutic areas, McCauley admits there are a few topics of particular interest. These include antimicrobial resistance, targeted radiotherapeutics and the so-called Omics space.

“Antimicrobial resistance is a very significant global problem, which has largely been abandoned by commercial organisations because of the technical challenges,” he says. “We believe there’s an opportunity to address some of those challenges, so we’re pretty intrigued by that. With targeted radiotherapeutics, we’re seeing some interesting opportunities to combine it with known and novel agents. Then in the Omics space there are significant efforts underway to harness genomic expertise together with human tissue banks to define novel targets and products.”

Image courtesy of the Centre for Drug Research and Development

Designing the ‘killer’ experiment

Even where a technology looks promising, there may be a few extra obstacles to getting the research off the ground. Sometimes the findings cannot be replicated (meaning it is all but useless from a commercialisation point of view) and sometimes it’s hard to define the technology’s true potential.

One of the ways that the centre can help is by designing the ‘killer experiment’ – i.e., the single experiment that makes the potential clear either way.

“There was an interesting piece of literature a number of years ago in Nature looking at about 400 approved products from about 200 companies, and it ranked the determinants of success of those programmes,” says McCauley. “The number one determinant of success was killing a programme early – obviously not because you do that, but because of what it says about you as an organisation. It means you ask the tough questions early and you look deeply. We can ask those critical questions on behalf of researchers and frankly that’s where we add value.”

The number one determinant of success was killing a programme early

Image courtesy of the Centre for Drug Research and Development

Spin-off companies solve unmet medical needs

So far, the CDRD has spun out seven companies that aim to solve unmet medical needs. These include Zucara, a diabetes company focused on long-term solutions to hypoglycemia; Sitka BioPharma, which develops novel oncology formulations; and Sepset, which is working on a rapid diagnostic test for sepsis.

“We’re pretty proud of the results we’ve generated – seven companies have attracted around $170m worth of risk capital, which is a strong testament to the depth of their research,” says McCauley. “One of the companies we helped found, Kairos Therapeutics, is an excellent example of the role we can play in foresighting. When we first got involved in the antibody-drug conjugate space, not many people cared about it or expected it to be successful, but we got together with a serial Canadian entrepreneur and built up the infrastructure.”

The company’s eventual success speaks for itself. Two years ago, Kairos was acquired by Zymeworks, leading to the creation of Canada’s largest biologics company. Since then, Zymeworks has attracted nearly $100m of additional investment, in part due to the Kairos platform.

The CDRD has spun out seven companies that aim to solve unmet medical needs

Image courtesy of the Centre for Drug Research and Development

Investing in training for the future

The CDRD also focuses heavily on training, with a view to helping young researchers transition to the industrial world. To date, 192 trainees have completed the CDRD programme, 96% of whom have gone on to relevant jobs in industry.

“In the next couple of months, we’re looking forward to announcing a similar programme on the business side, focused on training the next generation of life science executives in Canada,” says McCauley. “So as we’re building the anchor companies and helping companies scale up, we’re also contributing meaningfully to the calibre of personnel who will be leading those companies.”

The CDRD is helping Canada’s research base fulfill its true commercial potential

In February this year, the Canadian Government announced it was building five industrial ‘superclusters’ – Silicon Valley-style innovation hubs focusing on a range of technologies. Although digital technology, protein industries, advanced manufacturing, artificial intelligence and the ocean industries are all on the list, life sciences is not. This means the need for anchor companies seems particularly acute.

McCauley hopes this will not be the case for long. With ongoing support both from the government and industry, the CDRD is helping Canada’s research base fulfill its true commercial potential.

“We’re making a difference both in terms of Canadian industry, and in terms of the potential to bring new medicines to patients around the world,” he says.